Hội thoại

Kecho lab

30th March 2020 8:45 GMT

Đặng Ngọc Anh

Tue Nguyen

Alexander

Nguyen Thanh Thuy

Bireli

Todd

Dung Rau

Arthur

Phan

Dionisio

Sylia Kiese

Imran Peretta © Lenka Rayn H

Politics and personal experience combine in the films of Imran Perretta. The son of a Bangladeshi mother and an Italian father, he grew up in South London in a political landscape shaped by the Islamaphobic “war on terror” in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. His work reflects his acute awareness of the ways in which state aggression is enacted on young men of colour. He is also keenly concerned with the human impact of government policy on the lives of individuals. Last year Perretta was shortlisted for the Jarman Award for 15 days, a film made in response to the refugee crisis in Northern France, which arose out of time he spent with former inhabitants of the “jungle” who continue to live rough in the woods surrounding Calais, in particular one person whose assumed name gives the film its title. Perretta is also a musician and poet: his poems accompany his films and also act as their starting point. His most recent film commission is the destructors, currently showing at Chisenhale Gallery, London (until 5 April), and touring to the Baltic in Gateshead (opening on 14 March) and the Whitworth in Manchester. Shot on location in Tower Hamlets, East London and presented across two screens, it also uses his poetic writing, an atmospheric soundtrack and computer-generated special effects to explore the complexities of coming of age as a young Muslim man in the UK.

- Example of a cmplex sound communication channel, diagram from Abraham Moles, Information Theory and Esthetic Perception, 1958

- Painting

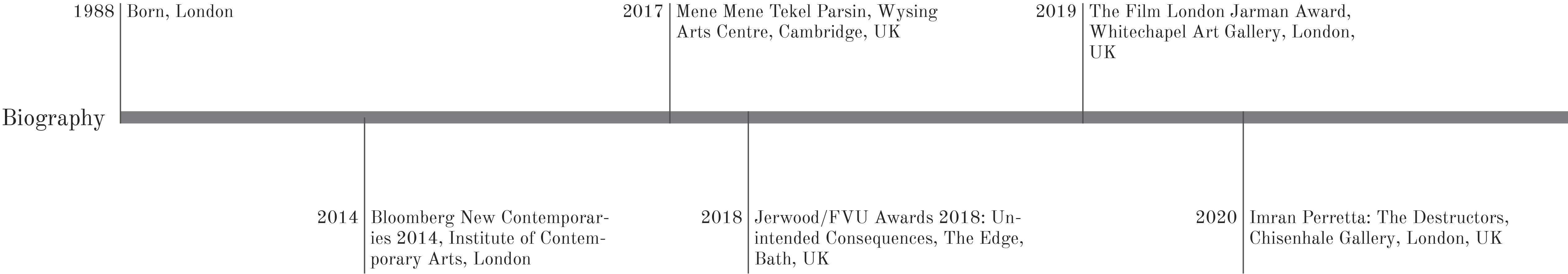

Timeline

The Art Newspaper: the destructors takes its title from a Graham Greene short story written in 1954 which is set in post-war London and follows a gang of young men who plot to demolish an old man’s house. What was it about this story that inspired you?

Imran Perretta: I studied it at school around the time the Twin Towers came down and it was also around that time that my body was growing at this exponential rate and I started to be seen as a public threat. I think reading the story about these young boys and how they were marked for their capacity for violence chimed with me because that was the way in which my body was also starting to be seen and it was a very uncomfortable realisation. The boys in the story were seeing this man’s house in a time of devastation just after the Blitz and I was interested in the parallel with the beginnings of the war on terror around the same time. So there were all these cultural and historical markers that meant that my narrative had this sort of eerie symbolic relationship with the narrative in the short story and this has always stuck with me.

In the film, three young men recount their different experiences—a violent encounter on a bus, the experience of being surveilled and the failure of the NHS to offer care for a terminally ill relative—in monologues based on your personal experience. Why was it important to relate events that had actually happened to you?

I was interested in talking about a specific experience of structural oppression and Islamophobia in the hope that, if I spoke very lucidly about some of the things I’ve seen, then it would resonate in one way or another with people who had seen or heard something similar. I was reticent to talk about political forces like austerity and the war on terror in generic terms or just as pieces of legislation when what they do is affect families and individuals in a very intimate way. So what I was trying to do was to use very intimate and personal experiences of having been wronged as a way of aiming upwards at the state and authoritarian politics. I’m coming from a position of trying to critique power structures that have laid a path for me, and I can only do that in an embodied way, otherwise I’d be a commentator rather than someone who has actually experienced these things.

Strange things happen to the building in which the film is set: it starts to fill up with water and smoke wafts in through windows and vents. It seems almost like a protagonist in its own right and under threat from outside forces. There are parallels with the building in Greene’s story.

The building is a community centre that is slowly falling into disrepair because the local council budget was under austerity measures. I wanted to draw attention to its slow decay and the fact that if you erode social provision, what you are eroding are communities, families and real people and so the building becomes a protagonist in the work. You see liquid and gas entering the space as this sort of ingress, these insidious outside forces creeping in as well as drawing attention to the fact that the building is porous and falling apart.

The water and smoke are computer generated and this use of visual effects is something that recurs in your work—why do you use this imagery?

The core interest for me is how to reference images from conflict and war without actually having to show them—how you reference violence, especially state violence and material devastation, without having to show the people or the places that have suffered in reality. That is really important. We have become so accustomed to seeing black and brown deaths on television and to seeing certain bodies treated with a certain sort of callousness and coldness by the camera. So for me it is how can you show and allude to violence and conflict without actually having to show its real-life effects? How to talk about the things we’ve endured without having to further endure them, that is part of the mission, the political strategy of the work.

I also have an interest in magic realist literature, particularly that which references colonialism, like Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children. It has this sense of the uncanny, of something that is very close to real life but is in some way extraordinary and abstracted and of using that distance, that suspension of disbelief to talk about things that are historically or culturally traumatic. For me visual effects tap into that idea of the uncanny and how you can create a slightly otherworldly scenario that is actually concretely rooted in the real world, and is almost truer than the truth.

The film’s soundtrack is another important element created by you.

My background is really in sound. I’m interested in how sound, regardless of context, can give a very embodied or visceral response in a viewer or listener. In that sense it’s a tool you can wield in very interesting ways cinematically. It relates to VFX in that I’m interested in the kind of soundtracks you find in war films and horror and thriller films and using them not to talk about espionage and grand action sequences or people running through the trenches, but for someone talking about their anxieties about the world or the situation they find themselves in. It’s this really affective, effective tool for personifying anxiety and depression but also love and joy and care. So for me sound becomes a way of creating both dissonance but also consonance in the work. In a lot of ways the writing comes first, the sound comes second and the image comes last in my thinking, it’s definitely a very important part of what I do.

In the destructors and most of your films you rarely see the full faces of the protagonists—why is this?

That’s very important. People of colour are rendered both visible and invisible at all times and against their will. There’s no better example of that than in the government’s Prevent Strategy and how it has forcibly made visible Muslim communities throughout the UK and at the same time has made them invisible in strategic ways. So you have this sense where you are made incredibly visible to the authorities but you can be detained and not seen by your family and friends for years at a time. Visibility becomes this key tool for agency that has been taken away by the state, so trying to crop people and trying to give them back their anonymity was a way of trying to give them back their agency. Surveillance seems to be a key theme in all your films, whether in your choice of camera angles, the way shots are framed or in the use of drones.

Surveillance is asymmetric insofar as how certain communities are surveilled more than others.

And I happen to belong to one that has been surveilled the most in a post-9/11 context. So my sense of self is invariably conditioned by the way I am seen by the state: I am hyper-visible and have been since I was 14 years old, the first time I was stopped and searched by the police. So part of me going on this long and winding road to becoming an artist film-maker is about trying to find a visual language for my own visibility but one that tries to resist the dominant or normative forms of cinematic and state visibility. I’m trying to find something else that can reference my visibility but also critique it. That’s really my mission, so to speak.